Peter King Hearings and A Lesson From 1921

By Nancy Fuchs Kreimer

Director of the Department of Multifaith Studies and Initiatives, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College

Posted 03/15/11 01:12 PM ET

Courtesy Of "The Huffington Post"

In the weeks leading up to the House hearings on "the radicalization of American Muslims," anti-Muslim rhetoric continued apace in some segments of the media. At an Islamic Society of North America dinner in Arlington, Virginia last month, over 200 Muslims shared their concerns as panelists discussed the challenges facing the Muslim community. Professor Ingrid Mattson, the immediate past president of the organization, began the program by reminding the audience, "We are not alone -- our interfaith family has our back."

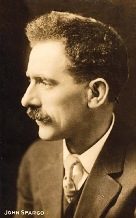

This is not the first time Americans of faith have stood behind a religious group singled out for suspicion. In 1921, at a time of widespread, virulent defamation of Jews, John Spargo, a lay Methodist minister, social critic and activist, said "It should not be left to men and women of the Jewish faith to fight this evil ... Anti-Semitism commands our special attention today ... but my plea is not for pro-Semitism." Rather, he opposed efforts to "divide our citizenship on religious lines." He did so out of "loyalty to American ideals." In a lecture later that year, Spargo called religious hatred "American treason." In his eyes, the "Jews' problem" was actually an American problem.

In the years immediately following the First World War, more than half the Jews in America were foreign born. As Spargo noted, "It is always difficult to avoid suspicion of the different groups we have drawn from other countries where there has been a barrier of language, creed or customs." Efforts were underway that would, by 1924, radically restrict immigration. A revived Ku Klux Klan, dormant since 1870, gathered force. Within the context of rising racism and xenophobia, Spargo was particularly outraged by the level of bigotry directed at Jews.

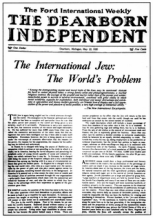

In February, 1920, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer published a report entitled, "The Case Against the Reds," in which he asserted that the Department of Justice had discovered "upwards of 60,000 ... organized agitators ... in the United States," while broadly hinting that many were Jews. That same year, Henry Ford, the leading industrialist in the country, introduced the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to American readers, printing the first of a series of articles titled "The International Jew: The World's Problem," in newspapers that he owned and widely distributed. Never before (or since) have Jews in America felt so vulnerable.

Not unlike Muslim Americans today, Jews were a diverse community that sometimes disagreed over strategies and tactics. The American Jewish Committee, founded in 1906 by American Jewish lawyers and businessmen concerned for the fate of Jews in Russia, debated how to respond to their own situation, as did the more recently created Anti-Defamation League, begun in 1913 in response to the Leo Frank trial in Georgia. Should they consider litigation? Was a boycott of Ford cars too radical a response? Perhaps, some suggested, the recently published "Jewish Contributions to Civilization" should be widely distributed. Others thought to counter, point by point, the lies in the anti-Semitic literature.

What the Jews themselves could not have hoped to make happen, John Spargo did. The New York Times reported on Jan. 16, 1921 that, "A protest against anti-Semitic propaganda in the United States, bearing the signatures of President Wilson, William H. Taft, Cardinal O'Connell and 116 other widely known men and women of Christian faith, was made public here tonight by John Spargo, Socialist author." Signers included church leaders, secretaries of state, and university presidents. Among those who lent their names were William Jennings Bryan, Clarence Darrow, and W.E.B. Dubois.

What the Jews themselves could not have hoped to make happen, John Spargo did. The New York Times reported on Jan. 16, 1921 that, "A protest against anti-Semitic propaganda in the United States, bearing the signatures of President Wilson, William H. Taft, Cardinal O'Connell and 116 other widely known men and women of Christian faith, was made public here tonight by John Spargo, Socialist author." Signers included church leaders, secretaries of state, and university presidents. Among those who lent their names were William Jennings Bryan, Clarence Darrow, and W.E.B. Dubois.

Ninety years later, we find ourselves at another moment that calls for interfaith solidarity. After Congressman King announced his plans, 51 organizations, including Christian, Muslim, Unitarian and Sikh groups, signed a letter to the House leadership strongly objecting to the hearings. On Sunday, March 6, Jewish and Christian leaders spoke alongside Muslims at a rally in Times Square; some 300 people stood in the rain that Sunday bearing signs reading "Today, I am a Muslim Too." As the first day of hearings ended, an interfaith coalition held a press conference, announcing the official launch of Shoulder to Shoulder: Standing with American Muslims; Upholding American Values, a campaign of national faith-based organizations and religious denominations to promote tolerance and put an end to anti-Muslim bigotry.

John Webster Spargo would approve. He would also urge us to expand our ranks and make our witness stronger and more visible. Our interfaith family should assure Muslim Americans that we do, indeed, "have their back." That said, Spargo would remind us that the problem we are facing is not the "Muslim's problem." It is a problem for Americans. And we will address it ... shoulder to shoulder.

Rabbi Nancy Fuchs Kreimer is a member of the Steering Committee of "Shoulder-to-Shoulder".

No comments:

Post a Comment